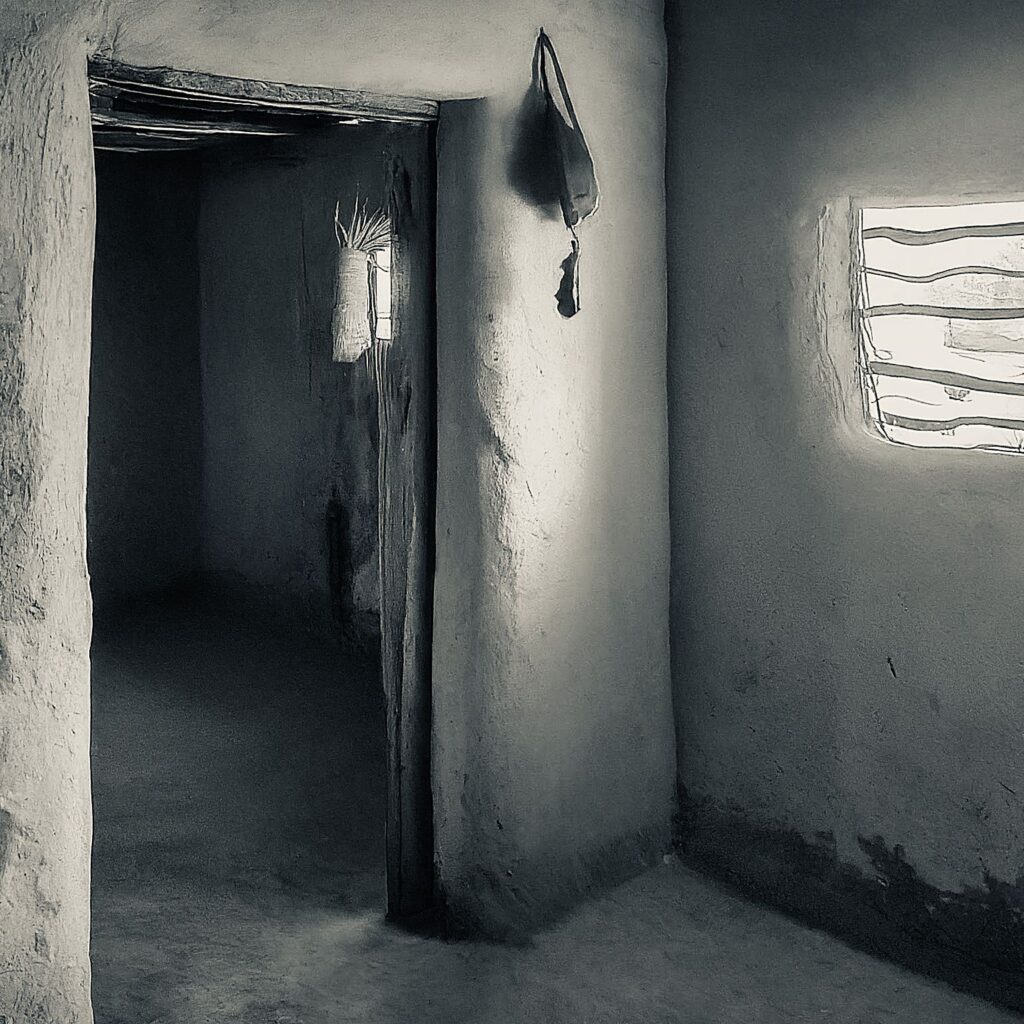

Nkanze is a smallholder farmer in the village of Gwoza in Northern Nigeria. Gwoza is a lively village. Down the narrow, winding roads that weave through the village, you will find humble homes built from local materials. These houses are called “karaboots,” and are constructed from straw, mud, and bamboo. They are basic and often in need of repair.

This is where Nkanze lives with her three sons. On the plains that extend beyond the village, the land is parched and cracked, mirroring the hardships she faces. If you’re thinking the Gwoza is some serene countryside scene with flourishing crops and ample water, you might be surprised. If you imagine the hardship is just the occasional struggle with finances, you’re highly mistaken. This isn’t the kind of poverty where missing a meal is the worst of it. No, Nkanze’s reality involves the harsher elements of life: poverty, drought, starvation, famine, pestilence, and war.

Two months ago, the town crier’s voice echoed through Gwoza at midnight, shattering the quiet with urgent news. The fear in his voice was palpable. So it wasn’t surprising that as his voice traveled through the village, anxiety gripped every household. Everyone awoke in a panic, reaching for their palm oil lanterns to illuminate the darkened huts. The announcement was grim: a cholera outbreak had struck the village once more.

Sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, were soon writhing in pain, their bodies ravaged by severe diarrhea and vomiting. The rapid spread of the disease claimed lives within a matter of hours, and the sight of their loved ones suffering was unbearable. With the medical center located miles away and access to treatment limited, the village faced an overwhelming crisis and Nkanze’s own world was shattered once again as she lost her husband, Ebenezer, to the disease.

Nkanze told CompassionLink during our visit, “We have no help, no hope, no support. We live every day knowing it could be our last if God does not help us. But we have learned to be strong and creative. I thought if the drought comes again, all my family will be killed. I had to do something…”

“We have no help, no hope, no support. We live every day knowing it could be our last if God does not help us. But we have learned to be strong and creative. I thought if the drought comes again, all my family will be killed. I had to do something. Where there is a will, there is a way.’”

Droughts have repeatedly ravaged Gwoza, turning once-fertile fields into barren wastelands. Each dry season brings the same fear—of crops failing, of hunger and diseases spreading, and of lives being lost to the relentless heat and dust. The previous drought was a particularly harsh blow. For months, the skies offered no relief, and the ground, cracked and dry, seemed to mock their efforts.

When we asked what the government was doing about it all, Nkanze’s response was a hollow laugh, tinged with bitterness and pain. “Government?? What government??” she asked, her voice cracking. “The ones who only come around to bribe our chiefs? Or the ones who promise change but never deliver? We have no government. Just a bunch of tyrants that come here every market day to collect taxes and leave us to fend for ourselves.”

Her words echoed the frustrations of many in Gwoza. The promises made by distant officials and the occasional visits from government representatives have amounted to little more than empty gestures. The village’s struggles have largely gone unnoticed, their pleas for help drowned out by bureaucracy and indifference.

When I asked Nkanze how she started sustainable farming, her face lit up with a mixture of pride and happiness.

“First, I and my sons made clay pots and big containers from local materials. We placed these pots around our fields to catch rainwater. When it rained, the pots would fill up, and we’d use that water to keep our crops alive during the dry season.”

“Next, we worked on making our soil better. We gathered things like plant leftovers and animal dung and used them as manure. This helped make our soil richer and more fertile. We also covered the soil with leaves and straw, which helped keep the moisture in and protected the crops from the harsh sun. To make sure the water went where it was needed, we built small irrigation channels from stones and clay. “

“We also started planting crops in sacks during the dry season. We’d fill these sacks with soil and compost, then plant our seeds in them. This way, even if the ground was too dry to plant directly, we could still grow food. The sacks helped keep the soil moist and gave our plants a better chance to survive.”

“It wasn’t easy, and it took time,” Nkanze said, “but every little improvement gave us hope. Without external support or loans, we had to make do with what we had. We had to work together as a community, pooling our resources and knowledge. Each successful harvest, each new plan that worked, reminded us that change was possible and that we could create a better future for ourselves and for Gwoza.”

Nkanze’s journey illustrates how eco-friendly agriculture is not just a method but a lifeline that brings new possibilities to those who need it most. Despite the lack of external support and the harsh realities of their environment, they have transformed their fields and their futures. Through each drop of rainwater conserved and each seed planted, they are cultivating more than just crops—they are nurturing hope, strength, and the promise of a better tomorrow.